By Tyler Hamilton, Daniel Coyle

£3.85 paperback Corgi (9 May 2013)

£12.72 hardback Bantam Press (11 Sep 2012)

£3.66 Kindle Edition Transworld Digital (12 Sep 2012)

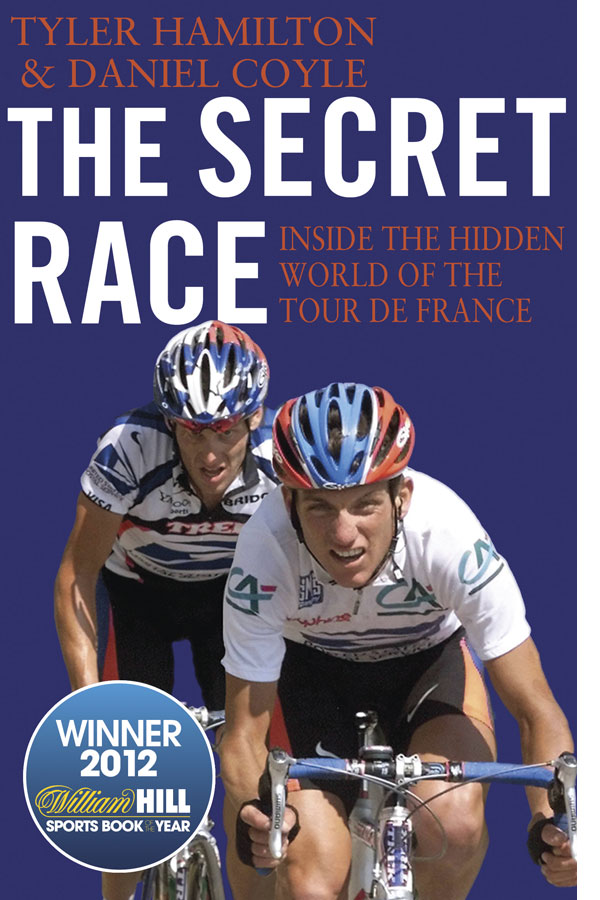

COVER IMAGE :

Review

For anyone passionate about sport and cycling in particular, this is a must-have book. From a narrative point of view it is well structured, but the story is so very compelling that it could be written in code and still keep you glued for hours (it is the book that forced Lance Armstrong to confess to the use of banned performance-enhancing substances or doping.)

Personally I had several questions in mind before reading the book. I found the answer to some of them, for example, if doping levelled off, or not, the performance, if Lance Armstrong was a victim or perpetrator, the treatment that was reserved for those who didn’t follow the rule of doping.

“But one of the biggest ways to piss off Lance was to complain about doping. Jonathan Vaughters was probably the best example of this. With his probing mind, JV wasn’t the kind of guy to accept doping at face value. He didn’t just do whatever Lance and Johan said. He asked the questions nobody asked: Why are we doing this? Why doesn’t the UCI enforce the rules? What’s more, JV was twitchy when it came to the doping, he was always worried about police, or testers. He even talked about feeling guilty – and guilt was an emotion most of us had given up long ago…..After the 1999 Tour, it was clear to everybody that JV didn’t gel with Lance and Johan’s system.”

I was moved by some of the previously unpublished stories about Italian cyclist Pantani, in particular by how he was feared by Armstrong for his instinct.

“Lance v Pantani, though, was another matter entirely. Pantani was impetuous, romantic, the kind of person who in a slightly different life would have been a bullfighter or an opera star. He wouldn’t rest until he made an impact on the race. Lance wanted things to be logical, and Pantani wasn’t logical, and Lance hated it.”

“The worst came on stage 16, from Courchevel to Morzine, when Pantani took off alone in the race, a suicide move we figured would soon end. But it didn’t end. Pantani kept driving the pace, he didn’t slow down, in fact he kept speeding up. We chased as hard as we could, but we weren’t reeling him in. There was only one thing to do: Lance told Johan to get Ferrari on the phone. The conversation was brief-I could picture Ferrari with his graph paper, running the numbers-and the answer came back:the pace was too fast. Pantani would crack. He could not keep this up. And Ferrari was right, as always. On the last climb, a nasty 12-kilometer ascent called the Joux Plane, Pantani finally cracked.”

It is evident at the end that the doping was systematic, not just a few isolated incidents (Pro cycling, on the other hand, follows a more Darwinian model: teams are sponsored by big companies, and compete to get into big races. There are no assurances; sponsors can leave, races can refuse to allow teams. The result is a chain of perpetual nervousness: sponsors are nervous because they need results. Team directors are nervous because they need results. And riders are nervous because they need results to get a contract.). A well-orchestrated system and that shows the complicity of everyone who had an economic interest: athlete, sponsors, mechanics, doctors, media/television. Thanks to this book, certain characters, amongst which (but not only) Lance Armstrong, can be considered examples: examples of what sport ISN’T about.

Subscribe to our newsletter to have the latest updates delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe to our newsletter to have the latest updates delivered straight to your inbox. TRI60 DISTANCE TRAINING

TRI60 DISTANCE TRAINING  Sportbox Training Focus Roma-Ostia Half Marathon 2019

Sportbox Training Focus Roma-Ostia Half Marathon 2019  Sportbox Training Focus Venice Marathon 2019

Sportbox Training Focus Venice Marathon 2019  t-shirt limited edition autographed by Danilo Goffi

t-shirt limited edition autographed by Danilo Goffi  Women's Sitting technical t-shirt

Women's Sitting technical t-shirt  Women's dove voglio technical t-shirt

Women's dove voglio technical t-shirt